The Hidden Impact of Microplastics on Ocean Ecosystems

Introduction

Beneath the waves of the world's oceans lies an invisible threat: microplastics. These minuscule particles, often smaller than a grain of rice, have infiltrated every corner of marine environments, from sunlit surface waters to the abyssal depths. While plastic pollution garners headlines for its visible toll—stranded whales and clogged beaches—microplastics operate in stealth, evading the naked eye but exacting a profound toll on ocean ecosystems. Recent studies estimate that there are over 170 trillion microplastic particles floating in the oceans, a number that continues to grow. This article explores the insidious ways microplastics disrupt marine life, food webs, and entire ecosystems, revealing why this hidden crisis demands urgent global attention.

What Are Microplastics?

Microplastics are defined by scientists as plastic fragments less than 5 millimeters in diameter. They come in two primary forms: primary microplastics, intentionally manufactured at small sizes (e.g., microbeads in cosmetics, exfoliants, or industrial abrasives), and secondary microplastics, formed by the degradation of larger plastic items like bottles, bags, and fishing nets through weathering, UV exposure, and wave action.

These particles are remarkably persistent. Unlike organic matter, plastics do not biodegrade; instead, they photodegrade into ever-smaller pieces, persisting for centuries. Fibers from synthetic clothing, shed during laundry, and microscopic tire wear from roads that wash into waterways are among the most prolific sources. Once in the ocean, microplastics become nearly ubiquitous, with concentrations reaching millions of particles per square kilometer in some gyres, such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

Pathways into the Ocean

Microplastics enter marine ecosystems through multiple routes. Rivers carry about 80% of ocean plastic from land-based sources, including urban runoff, wastewater treatment plants, and atmospheric deposition. Coastal activities—fishing gear, aquaculture, and tourism—contribute directly. Once afloat, ocean currents concentrate them in subtropical gyres, but winds and storms distribute them globally, even to remote polar ice.

A 2023 study published in Nature highlighted how microplastics hitchhike on floating debris, reaching seafloors via vertical transport. In the deep ocean, where pressures crush plastics further, they've been found embedded in sediments at depths exceeding 10,000 meters. This pervasive infiltration sets the stage for widespread ecological disruption.

Direct Impacts on Marine Organisms

The most immediate harm comes from ingestion. Plankton, the base of the ocean food web, mistake microplastics for food due to their size and shape. Zooplankton like copepods consume them readily, leading to reduced feeding efficiency, slower growth, and higher mortality rates. A landmark experiment by the University of Exeter showed that plankton exposed to polystyrene particles produced 50% fewer eggs.

Fish and shellfish fare no better. Small fish gulp down microplastics, suffering intestinal blockages, inflammation, and false satiety—eating plastic instead of nutrients. Larger predators, including seabirds, turtles, and marine mammals, ingest them indirectly or through prey. Necropsies of sperm whales have revealed tons of plastic in their stomachs, contributing to starvation.

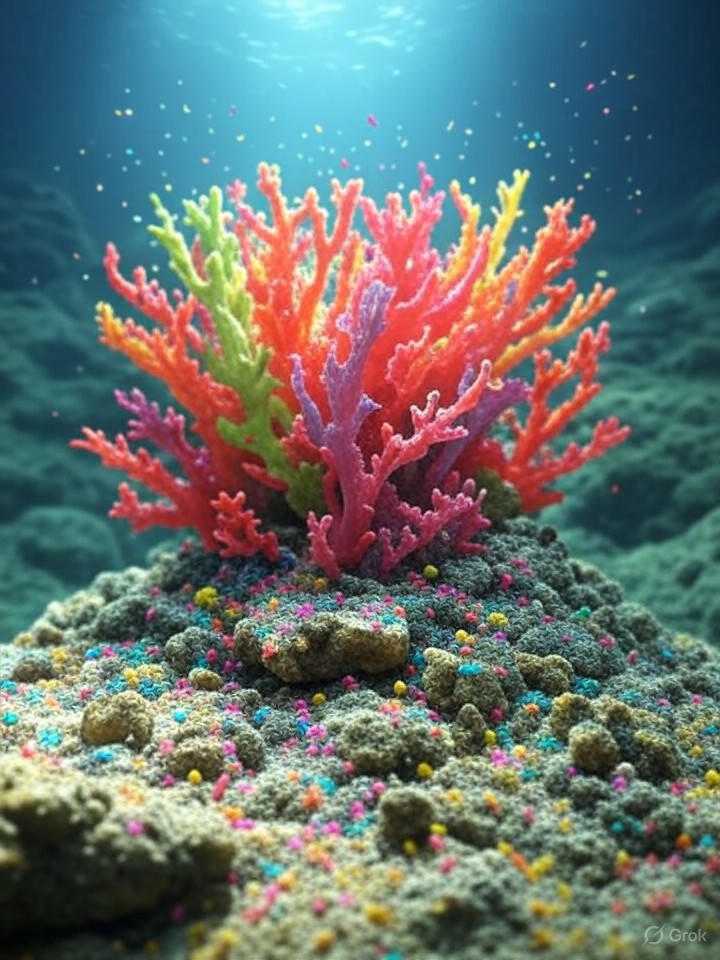

Beyond physical damage, microplastics are chemical sponges. They adsorb persistent organic pollutants like PCBs and DDT from seawater, concentrating toxins up to a million times ambient levels. When ingested, these leach into tissues, disrupting endocrine systems, impairing reproduction, and causing DNA damage. Corals, vital reef builders, suffer too: microplastics smother polyps, promote bacterial infections, and bleach symbiotic algae, exacerbating climate-driven decline.

Ripple Effects Through the Food Web

Microplastics propagate harm up the trophic ladder via bioaccumulation and biomagnification. What starts with plankton accumulates in fish, concentrates in predators like tuna, and reaches apex species such as sharks and orcas. Humans, at the top, consume microplastics through seafood— an average person ingests the equivalent of a credit card's worth weekly, per a 2019 WWF report.

This transfer alters ecosystem dynamics. Toxic-laden prey reduces predator fitness, skewing population balances. For instance, polluted forage fish may reproduce less, starving seabird colonies. In the Arctic, microplastics in sea ice are melting into food chains, threatening polar bears and seals already stressed by warming.

Behavioral changes compound the issue. Studies on fish show microplastic exposure impairs navigation, predator avoidance, and schooling, making populations more vulnerable to overfishing and collapse.

Broader Ecosystem Consequences

At scale, microplastics erode biodiversity and resilience. They foster "plastispheres"—biofilms of microbes on plastic surfaces that include pathogens and invasive species, outcompeting natives. In mangroves and seagrasses, carbon-sequestering blue carbon habitats, microplastics reduce sediment quality and plant health, weakening coastal defenses against erosion and storms.

Ocean chemistry shifts subtly: micropl